Literally the web

Where nothing refers to anything, and that's its problem

Pronouns are going to be dead soon, and not for the reasons you think.

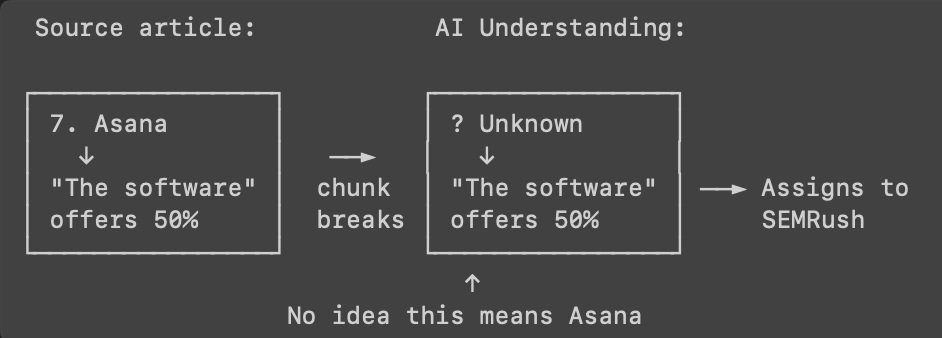

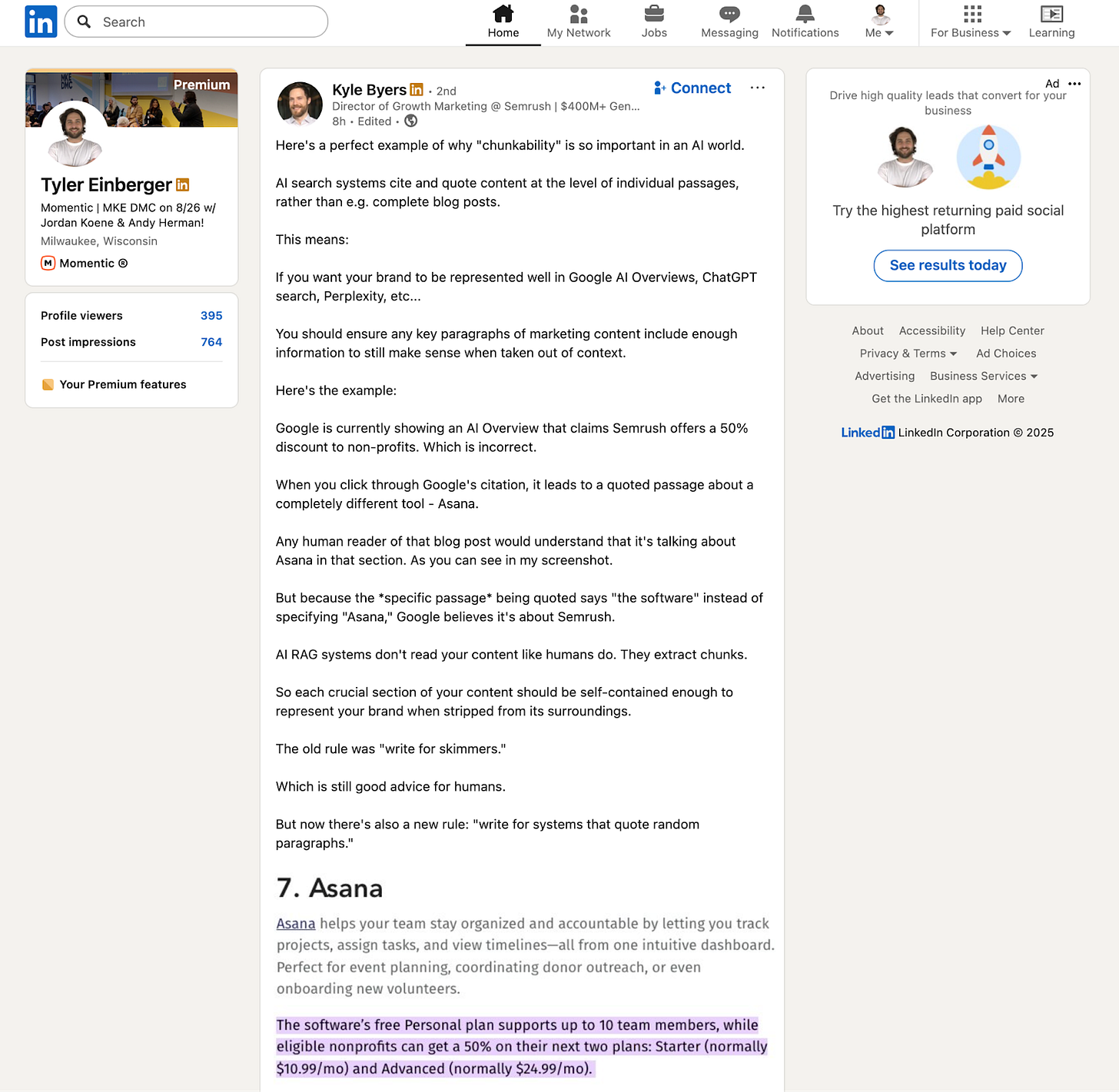

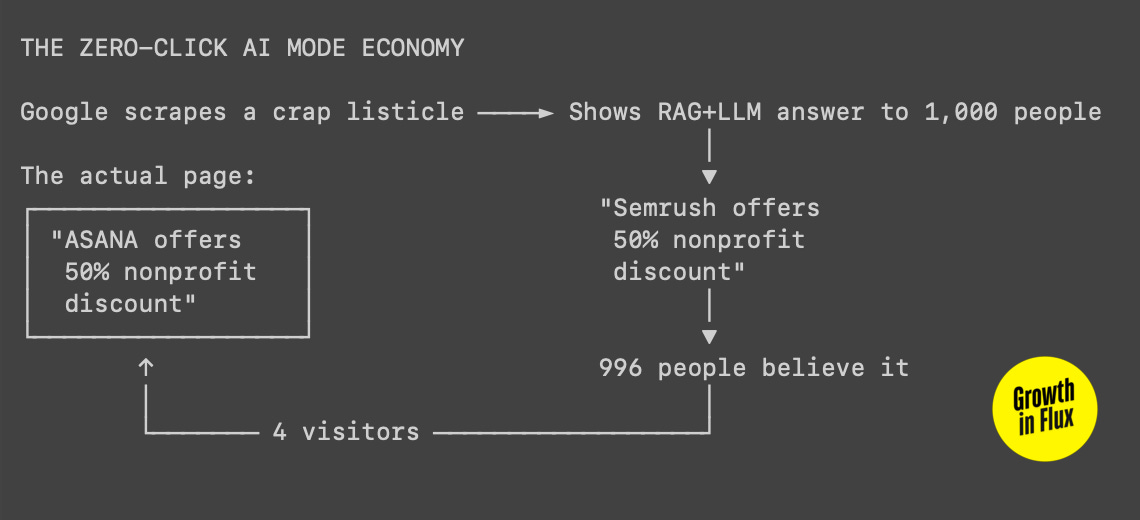

Kyle Byers posted the screenshot on Friday at 7 AM Pacific, and I haven't stopped thinking about it since. Google's AI Overview was telling searchers that Semrush offers nonprofits a 50% discount. They don't. That's Asana's discount, from entry #7 in a listicle about nonprofit tools. Semrush was only mentioned in the article as an example of expensive software to avoid. But between entry #7 and wherever Semrush appeared, the phrase "The software offers" lost its anchor, and Google's AI inverted the entire point: gifting a discount to the very tool the article warned against.

Zero clicks to clarify. Zero clicks to correct. We’re left with a machine's interpretation, served in an AI Overview as truth.

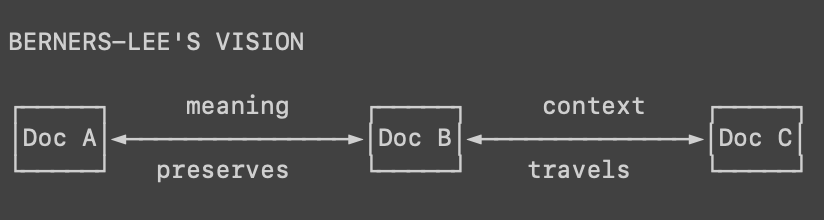

I spent the next three hours thinking about what is happening to language on the web. Not that SEO or AI slop hasn't mostly ruined that already. I went down the history of the web rabbit hole. Tim Berners-Lee's original vision, the semantic web that never happened (or is just beginning), the gradual enshittification of everything, including what we write online. It was killed somewhere between keyword stuffing and machines that read like goldfish with brain damage. I started with early HTML specs, ended up at Morozov's tech solutionism takedowns, and realized we'd already surrendered before the war began.

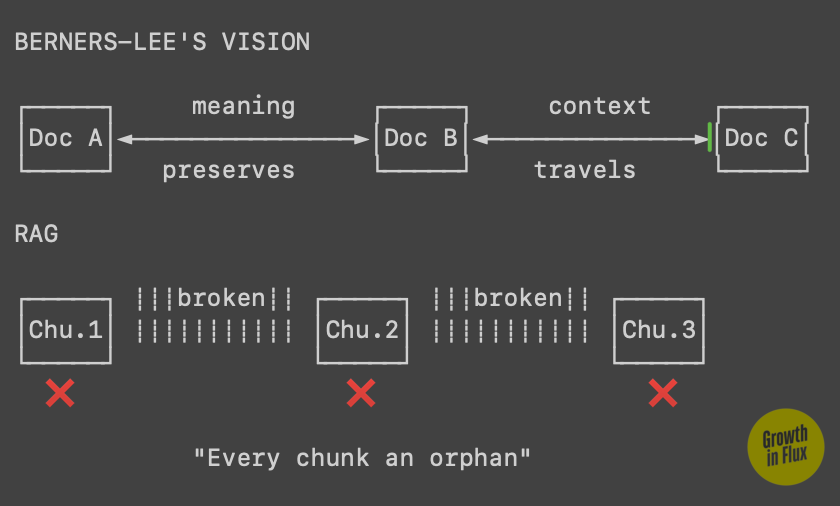

The web was supposed to be connections, links, context traveling between documents like electrons through copper. Berners-Lee imagined hypertext that would let meaning accumulate across sources. Instead we got keyword stuffing, private blog networks, programmatic SEO, and now machines that interpret source content like a seven-year-old on amphetamines.

Kevin Indig's analysis from last week laid out traffic patterns that are more like extinction events. Publishers are down 15-45% from AI Overviews alone, some are seeing 70% drops since April. The Atlantic is preparing for zero Google traffic. Not reduced. Zero. Data says the age of clicks is ending and being replaced by machines that read everything and send no one anywhere. OpenAI scrapes content 179 times for every actual human visit. Anthropic is 8,692:1. Perplexity is 369:1.

Garrett Sussman gives us deeper insight. Only 4.5% of AI Mode sessions generate even one click… as in singular, as in the statistical equivalent of zero. And new data points will continue to emerge like a bad rash.

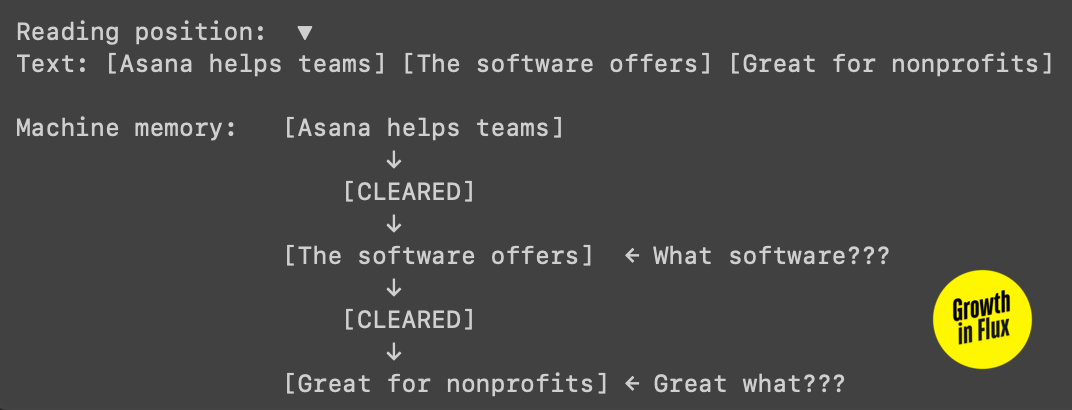

RAG systems chunk text, typically into overlapping token windows, for embedding and retrieval. But these chunks aren't semantic units, because semantic chunking is typically resource intensive. They're arbitrary slices that often split mid-sentence, and they carry fragments of meaning that the retrieval algorithm treats as complete thoughts.

When the RAG system chunks that listicle, "The software's free Personal plan" might land in the same chunk as part of entry #8, or in an overlap zone between entries, or orphaned in its own fragment. During retrieval, when someone searches for "nonprofit software discounts," the system might surface chunks containing both this orphaned discount reference and mentions of SEMRush from elsewhere in the article. The embedding model creates vectors, and cosine similarity between chunks containing 'software... discount' and 'SEMRush' might be high enough to retrieve both, even though they're semantically unrelated; producing a Frankenstein answer stitched from pieces that were never meant to connect.

Multiply this by billions of chunks and you get the new semantic web, where nothing refers to anything.

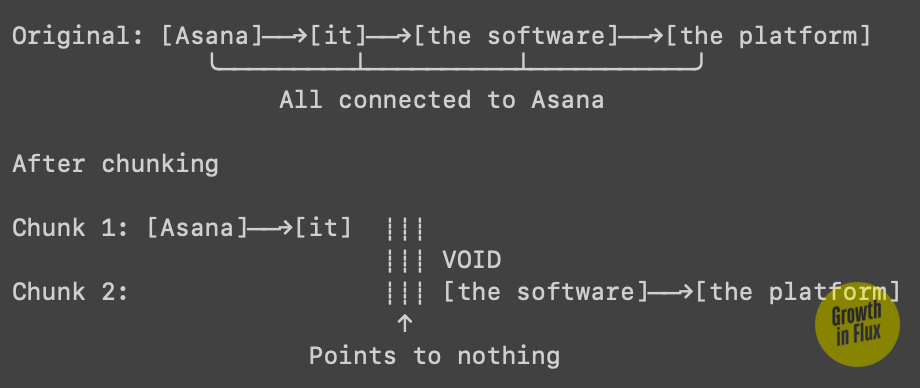

The technical term for what's breaking is anaphora resolution: tracking pronouns and references across context. When I write "Asana launched in 2008" and follow with "It now serves millions," you understand that "it" refers to Asana. This is so fundamental to human communication that linguistics considers it a universal feature of natural language. We build meaning through chains of reference, each sentence inherits context from what came before. But when text gets chunked for retrieval, these chains get severed. The system might retrieve chunk 2 without chunk 1, leaving "it" pointing at nothing.

But when documents get processed for retrieval, they're chunked into discrete units that get embedded, indexed, and searched in isolation. The economics of scaling to web-scale content makes storing full document context prohibitively expensive. So these systems retrieve fragments: quick chunks that match your query but lack the original context.

The result is a retrieval system that exhibits selective amnesia. It can find the statement perfectly while having no access to what preceded it. It surfaces facts but not their relationships. When these fragments get fed to an LLM for synthesis, even the smartest language model can't reconstruct connections that were severed during chunking.

This would be interesting if these systems remained research curiosities. But they've become the primary interface between people and information. When Google's AI Overviews generate “approximately zero clicks” to cited sources the machine's interpretation becomes the only truth that reaches an audience.

The result is a new kind of reader that exhibits what we might call selective semantic amnesia. It can quote your paragraph perfectly while forgetting what preceded it. It remembers facts but not their relationships. It processes language without maintaining the coherence that makes language language.

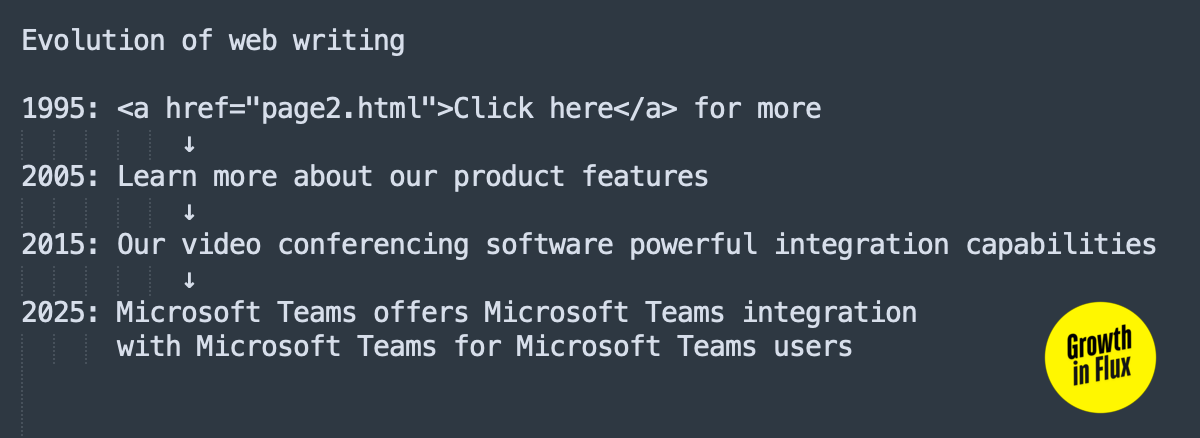

The industry’s response has been... “Well you must CHUNK text,” which other than being semantically false (writers write, systems chunk), means we’re surrendering to the machines. Writers will now repeat entity names obsessively: "Notion's collaboration features make Notion ideal for teams who need Notion's real-time editing." It reads like a concussion but communicates well with machines.

Watch the mutation happen:

Human English: "We launched our CRM in 2019. It now serves over 10,000 businesses with industry-leading automation."

Machine English: "Salesforce launched Salesforce's CRM in 2019. Salesforce's CRM now serves over 10,000 businesses with Salesforce's industry-leading automation."

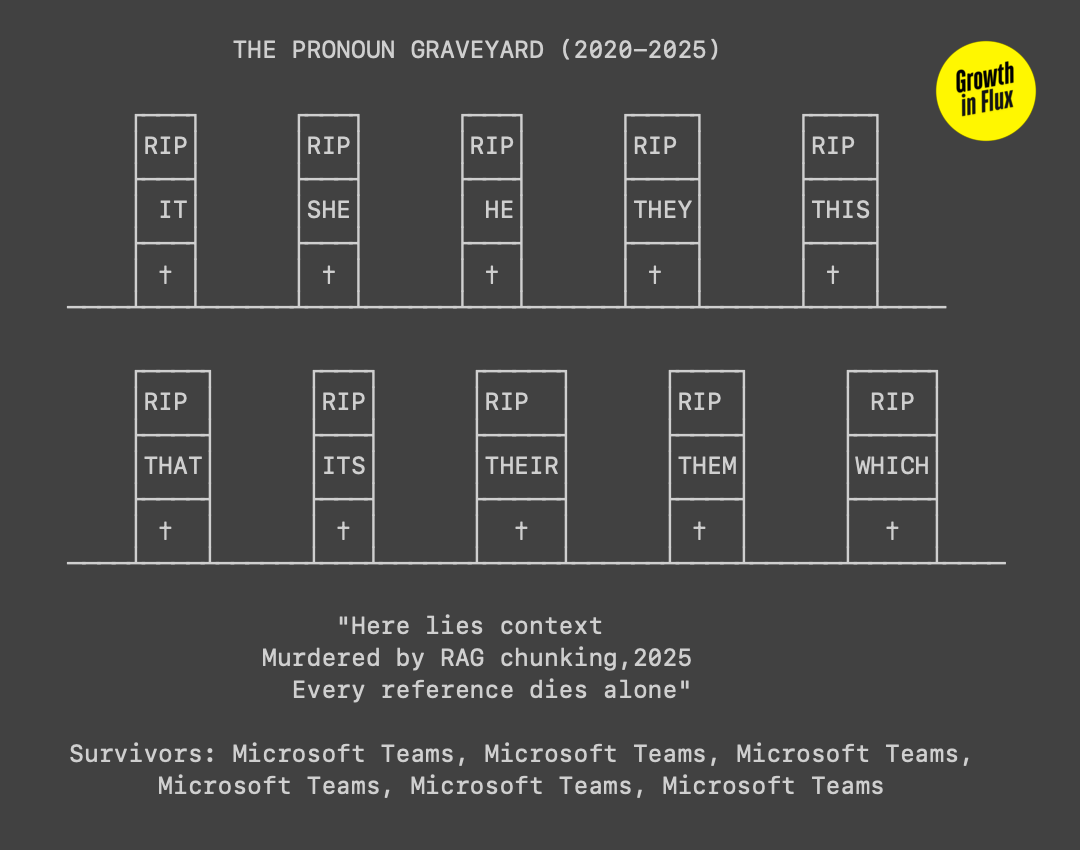

The pronoun is murdered. The reference is explicit. The sentence is wearing a syntactic awareness name tag forever.

Our best hope is that we maintain dual content strategies; one version for the humans who barely visit, another for the systems that do the visiting for them.

We're told this is optimization, but it's closer to capitulation. Every time we restructure human communication to accommodate machine parsing, we're changing language itself. The defensive repetition, the context-free paragraphs, the death of elegant variation. And it’s sad that these aren't temporary adaptations. They're the early stages of a shift in how we write, talk, and communicate forever.

The mechanism is that dependency creates deformation. As traffic patterns shift from direct visits to AI-mediated responses, publishers who want to survive must write for their new readers. But these readers impose constraints that are antithetical to natural language. They require a kind of writing that maintains no state, assumes no memory, builds no narrative flow.

What emerges is a dialect of English optimized for machines; call it Machine Readable English (MRE). Its rules are: Every sentence stands alone. Every reference is explicit. Every attribution is defensive. It is language stripped of the very features that make it efficient for human communication.

It’s kind of like keyword stuffing, but worse. Stuffing was gaming a system while maintaining human readability. This is restructuring human expression at its foundation. We're not tricking algorithms; we're becoming algorithmic ourselves.

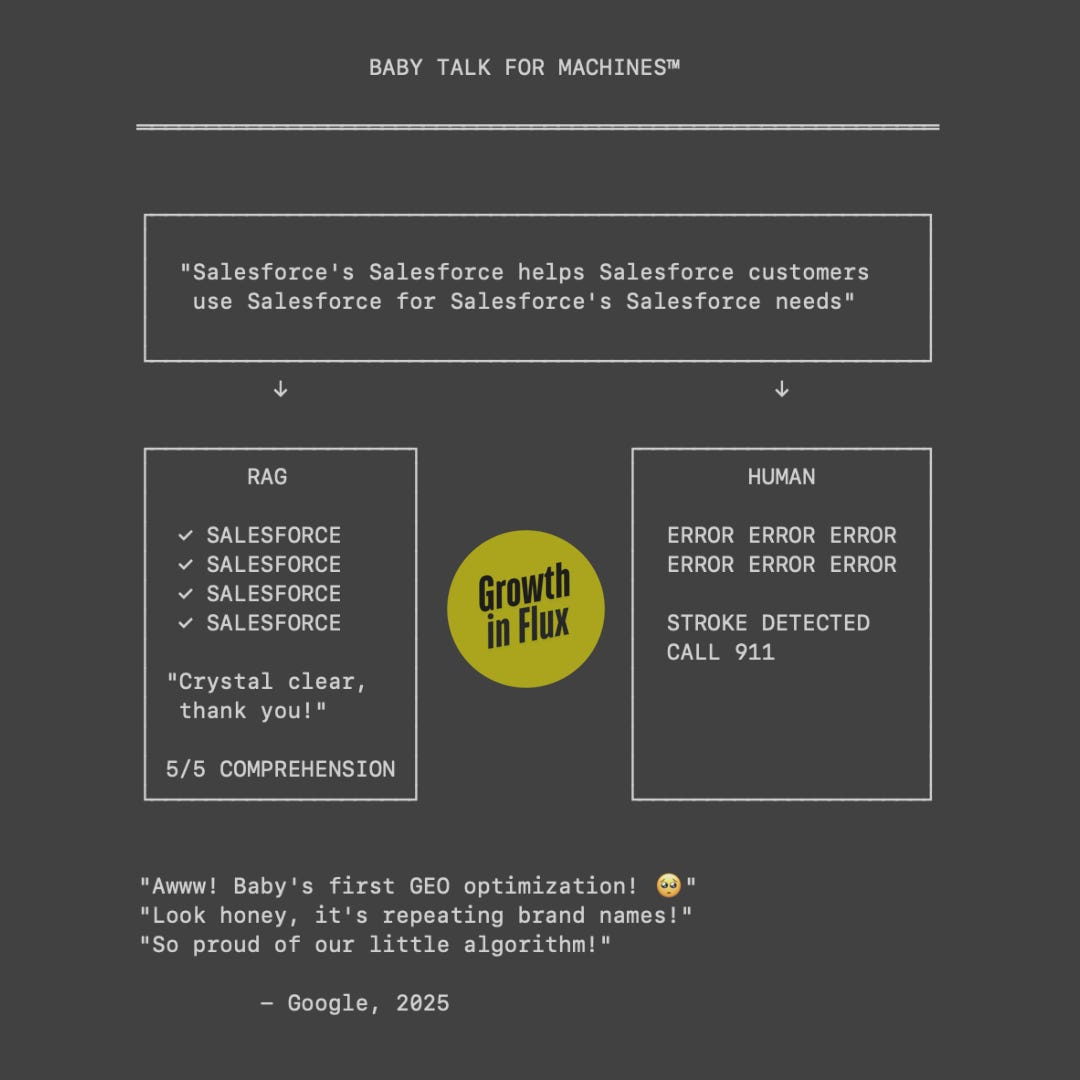

Theodore Adorno once wrote about how the culture industry's standardization doesn't just affect what we consume but how we think. The same process is at work here, but accelerated and more invasive. When we write "Salesforce's CRM helps Salesforce users manage Salesforce contacts," we're training ourselves to think in chunks. When we can't use pronouns, we can't build complex arguments. When every paragraph stands alone, we can't develop ideas across pages. When context can't travel, thought can't accumulate. And so we’re without memory. Without the ability to connect this to that to the other thing.

The publishers' dilemma illuminates the broader crisis. When The Atlantic's CEO tells employees to assume Google traffic will reach zero, he's acknowledging reality: the web is bifurcating into human spaces and machine spaces, and the machine spaces are eating the human ones. The economic incentives all point in one direction. Toward the literal, the explicit, the defensively clear.

But clarity and explicitness aren't the same thing. Human clarity emerges from context, from the careful building of understanding where each sentence enriches the last. Machine explicitness demands the opposite: each unit of meaning isolated, self-contained, atomized.

This is baby talk for machines. Language reduced to its most literal elements, stripped of style, variation, and flow. It's efficient for machines, exhausting, not to mention, unmemorable for humans, and increasingly mandatory for anyone who wants to be understood in a zero-click world.

The tragedy isn't that machines can't read between the lines. It's that we're forgetting why we put anything there in the first place. When we accept that every sentence must stand alone, we lose the ability to build ideas that require connection, development, nuance. We lose the essay, the argument, the story… all the forms that depend on maintained context.

This isn't technological determinism. We could build systems that maintain context, that read sequentially, that preserve the full richness of human expression. But those systems don't scale to web scale, don't deliver instant answers, and don't maximize engagement metrics. So we get machines that read like amnesiacs, and we adapt our writing to match their limitations.

The pronoun becomes a casualty of scale. And with it goes something harder to measure but essential to human communication: the faith that our reader is traveling with us, maintaining the thread, building understanding across time.

We’re all going to end up writing for machines simply because the economics demand it. But we’re not optimizing content. We’re participating in a restructuring of human expression. We’re helping machines build a web where context can't travel between paragraphs. And, it’s not because it's impossible, but because we've agreed that it isn't necessary.

The machines won’t get better at reading between the lines if we get better at having nothing there to read first.